Moments Like These: Rick Bryant

Moments Like These: Rick Bryant

Rick Bryant has enjoyed a lifetime in music. Even during his recent incarceration, Rick continued to create for life after jail. He could have had a strong career in academia, but the blues, folk, rock and soul was his calling. He is a resilient, literate and genuine solid citizen who has contributed much to a broad spectrum of local roots music, including stints with Original Sin, Mammal, BLERTA, Rick Bryant and the Jive Bombers, The Jubilation Gospel Choir and the Windy City Strugglers. It says plenty that a caricature of Rick was the cover of John Dix‘s NZ rock history Stranded in Paradise. That’s got to be as good as any lifetime achievement award.

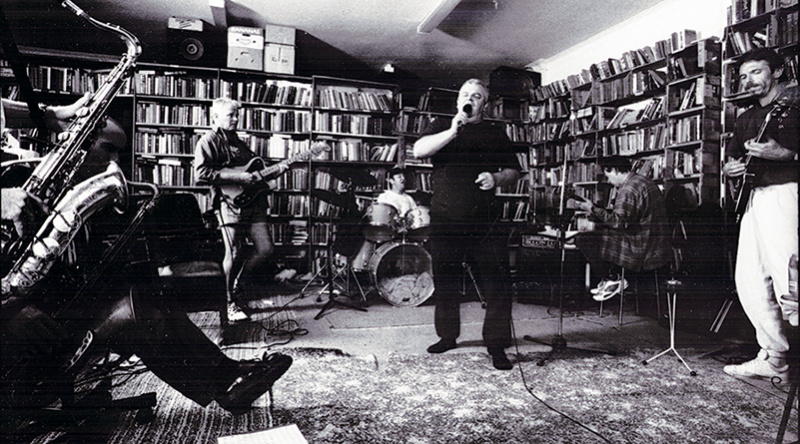

Jive Bombers at Green Door Books, Auckland 1997. From left: Michael Croft – tenor sax, Chris Watts – tenor sax, Wayne Baird – guitar, Rick Cotter – drums, Rick Bryant, Tony McMaster – bass, Cadzow Cossar – guitar.

When and where was this shot taken Rick? What’s the background to it?

This is a photo of the late 90s Jive Bombers line-up and was taken 1996, or thereabouts, by Robyn Sutherland who was one of our singers. It is a practice, not a recording session, at Green Door Books. At that time the band was morphing from a theme-park R&B standards band into a vehicle for original songs.

I was making an album called ‘Time’, at home, with John Kempt as engineer and producer, and realising that this was the way forward, creatively if not commercially…Through the 60s, 70s, 80s and most of the 90s I had been captive to the notion that performance was everything, and that the only recording that counted was live performance with an audience, in a venue. It was John who taught me to use my ears, and that the recording studio is the ultimate instrument. As with everything else, I was a slow and late learner.

Mike Croft has been with me on baritone sax since 1982, and former Jive Bombers members are always likely to come back or guest, but it’s actually been at least five different bands really, with some overlaps. I prefer stability of course. It started as a cover band with an aspirational agenda, and mutated gradually into the band that played what I was trying to write.

We have a Jive Bombers album called ‘The Black Soap from Monkeyburg’ ready to go.

How did you get started in the music business?

After spending my school years struggling with my fear of the audience I finally, nervously and briefly joined a band called The Changing Times, but was immediately fired for requesting to do Pretty Things covers. But it was too late, I had done my first gig, and discovered what it was that I was meant to do.

Actually, I think I have never had a start in the business. I’ve tried to get work as a singer, quite persistently. But I don’t do ads. I got bugger all TV work when it was going. I had one sponsorship, but that was a fluke – I struck an adman who loved R&B. I never got close to a record deal when the majors were doing them with all sorts of acts. And I’m certainly not in the business now.

But there is something else. The first successful group I was in was Mammal, who did R&B-influenced acid rock with the emphasis on acid, and would always be too strange for the majors. Then I was in Blerta for a bit – and they actually had a deal, but I got busted at a bad time. As if there were a good time.

Another thing is that I don’t think I was all that good a lot of time. I mean I was good enough that Bruno rang me from Sydney more than once asking me to go across to Blerta, so I must have been okay sometimes. But I drank too much and I lacked discipline. I chose to ignore what mainstream radio audiences, or their marketing consultants, really wanted to hear. So I don’t blame a system or a conspiracy for my indigency.

Some of my peers have done really well being themselves and selling good, I mean really good, versions of pop music, but I like archaic minority appeal styles, and I – what’s the word? – hate a lot of pop.

Playing live is not always a glamorous experience. Tell us some highs and lows of your touring existence?

Well, I’ll tell the approximately inclusive story in a book that I’ve started but – briefly, I’ve slept on more concrete floors than most people. In cars, a few times under cars… I live in a cold shed now. I don’t give it a thought, it’s where I work and I don’t want change, I want to stay focused.

But I’ve had a good run with audiences and they’re still my drug of choice. When the Strugglers played in England and France I realised that we were exportable. At our first show in London, I talked to three promoters who wanted to talk engagements, but it would have meant going home to NZ and immediately getting back to the UK again and we weren’t ready, although I wish we could have been.

So – I still want to work, to do gigs, as often as I can, with the proviso that I don’t want to be my own publicist, accountant, promoter, driver, roadie, tour manager, and FOH engineer, as well. A lot of people find that a bit much, although a few remarkable people cope. And yes, I’d like to get paid properly a bit more often.

But there is a rule – anyone who has paid to hear you deserves your best shot, no exceptions. It doesn’t matter if it’s six people or 6000.

You are a reader as well as a writer. How does the creative process work for you?

Different ways on different days. I am extremely fortunate to work often with a songwriter, Gordon Spittle, who is very easy – easy going, easy to solve compositional problems, easy to write with. (Well he makes it look easy – I’m not sure it is.)

I am the singer and he is the guitarist or sometimes pianist. He does the structure and I do the decoration. He is a real tunesmith who has a big chord vocabulary and bloody big hands to play full-size shapes – so we write ballads as well as rockers, R&B, almost anything in the wider genre.

I also work with Ed Cake, who is brilliant and from whom I learn a lot even though we do different music, which only sometimes intersects. And I learned a lot from John Kempt who lives in the US now.

To me the creative process can be a dialogue – I do a lot of lyric writing in solitary, but some of it has to be in a workshop situation. These days there are a lot of people who I can and do write with; Bill Lake, Tommy Ludvigson, John Malloy, for instance, using different players for different sounds and traditions. Singers too. I’m very lucky. Very, very lucky.

Teamwork is something I’ve learned to enjoy. I always knew that the drummer and the rhythm guitarist are the dance-motor for the singer. When you’re on stage you need to be with someone who loves to be there because they’re really good and they know that their talent is enjoyed and understood.

As you go on, you sometimes have the luck to be with a strong team, where everyone is doing their best and there are no passengers. That can be magic, and for rock or jazz musos, it IS the creative process. I’m sure it applies to other kinds of music too.

And your discipline is whatever it took to make that happen.

You’ve worked in many bands with a who’s who of influential or impressive musicians. What makes for a band that can last the distance like The Windy City Strugglers and the Jive Bombers?

There’s quite a lot of it around nowadays – longevity could be catching on. But if you look over the life of all music globally and historically, you see it was ever thus.

With the Strugglers there is a very strong bond of a shared taste for the flavour of Memphis music of the 20s through to the 70s, several decades of what can loosely be called the blues. I think we all have a somewhat curatorial perspective – the band is a statement about a kind of music, as well as being fun to play in.

The Jive Bombers is about stubbornness mainly. Mine. As a singer, I like to have the sonic support of a big horn section and the sweet inspiration of friendly females. It’s a popular template, but usually unaffordable. Well, I do what I can to afford it and do a few gigs to get what we write out there in my preferred format.

You give the impression that you have never compromised your lifestyle, but I wonder if there have been times when you’ve thought, “What am I doing this for?”

You are absolutely right. There has never been a time when I don’t feel quite often that it’s all just one mistake after another.

But, as I say, the audience is the drug and as long as people let you know emphatically that they’ve enjoyed your show, as long as people ring up and want to book you because they want to hear you again, as long as there are tasty gigs deep in the provinces of a beautiful country that isn’t completely ruined by big business yet, as long as it’s the best buzz there is, knowing that you’ve delivered the fun yet again, I’ll be doing it.

It was plan A, and when I considered other plans, I had to concede that plan A wasn’t much of a plan, but it was the only plan I had. So I’m sort of committed now.

You currently have Ed Cake ensconced in your library/studio, that probably makes for wonderful music acoustics. Tell us how this relationship and recording facility came together?

I went to a Tim Finn gig and was impressed with Neil Watson who was in the band. I asked Neil to help me out with some guitar and he started doing some of his own sessions in my room, which I had just got to the point where we could make really good recordings.

I went to France with the Strugglers and when I got back there was this seriously gifted individual working at my place who seemed to have got ensconced, yes, right word, by working with Neil. That was Ed, the Cake part of Bressa Creeting Cake, who I knew to be very able and well thought of – and who were what I think of as serious musicians – but not solemn or nerdy.

I realised that I could learn a lot from Ed and that although our music was very different a lot of the time, his perfectionism and energy – and creativity made him quite a lot like my mate John Kempt, who had gone to the US, depriving me of co-writer, producer and engineer.

Ed had a record to make and so did I, and he liked my room, which had finally come together after several years work, so we had an instant arrangement. He got on well with my writing-arranging-demoing song development team and the engineer I was working with already, Naz Noronha.

And I met a lot of good younger musos through him, and quite a few of them did some work with him here. Notably, Geoff Maddock who has also been a big help doing sessions for various projects.

Then just before I went to jail we did a gig at the KA with Ed, Geoff and Ross Burge, which we call the Straights. I was very pleased with that outing, and I can’t wait to do it again. Although I enjoy big line-ups, I can also enjoy minimalism, and the Straights’ sound is simple and clean.

Ed produced our soon to be released Jive Bombers’ album, ‘The Black Soap from Monkeyburg’, and I am very grateful for his judgement, attitude, and highest quality workmanship.

What’s the most important thing you can pass on to a young person intent on being a musician as a career?

You must expect to work really hard, be nice to people you instinctively distrust and dislike, and endure lack of privacy, security, stability, income, respect and a fair go. But if you can please a crowd, there will be compensations.

I have a very good friend, great player, whose advice would always be, “Give up”.

The best advice you ever got was…?

Mark Hornibrook, the last bass player in Mammal, who had been a National Youth Orchestra trumpet player, which I think meant you were more or less a cadet for the NZSO back then, told me, “There are two kinds of musician, the ones who listen and the ones who don’t. Every second you bother playing with a non-listener is utterly wasted.” I often think of that as good advice.

- bill lake

- blerta

- bressa creeting cake

- cadzow cossar

- chris watts

- ed cake

- edmund cake

- edmund mcwilliams

- geoff maddock

- gordon spittle

- jive bombers

- john kempt

- john malloy

- mammal

- mark hornibrook

- michael croft

- mike croft

- moments like these

- national youth orchestra

- naz noronha

- neil watson

- october/november 2012

- rick bryant

- rick cotter

- robyn sutherland

- ross burge

- the changing times

- the straights

- tim finn

- tommy ludvigson

- tony mcmaster

- trevor reekie

- wayne baird