Moments Like These: Doug Jerebine

Moments Like These: Doug Jerebine

Born on New Zealand’s North Island in rural Tangowahine, Doug Jerebine, aka Jesse Harper, first established himself as a guitarist with a reputation in Auckland bands including The Embers and The Brew during the early 1960s. However, for Doug it wasn’t to be all about hedonism and heroism.

An interest in Indian music shaped his spiritual beliefs and directed much of his adult life. Before making the pilgrimage to India, where he was to remain for almost four decades, Doug detoured to London, adopted the name Jesse Harper, and in 1969 recorded what would become known as the ‘lost’ Jesse Harper album. Having settled back in Aotearoa after an absence of 40 years he has landed a release for that forgotten album with Chicago indie label Drag City. Doug Jerebine is gigging and recording again, his extreme guitar wizardry proving remarkably intact. Trevor Reekie presents Moments Like These.

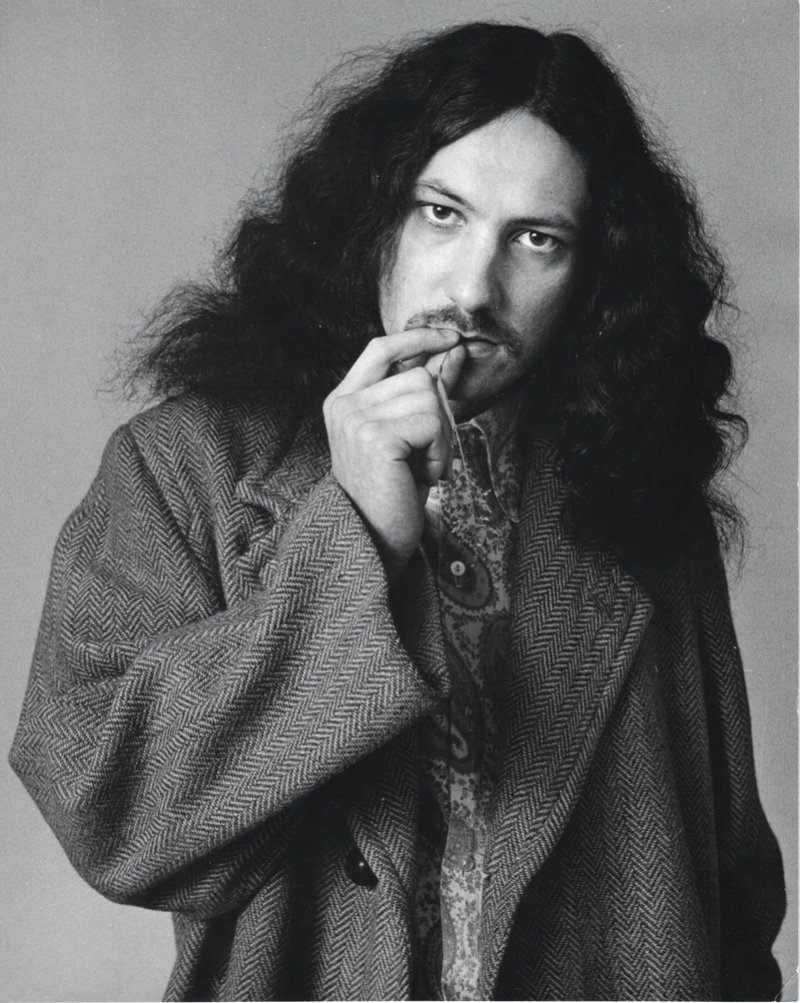

Where was this photo taken and what can you remember of the day?

This photo would be in 1968, the year I left NZ for UK and subsequently India. I played with Raman Bhai Chhibba in public three times, as far as my memory serves me. Once was at the Gandhi Hall, another was at a Hindu wedding function and another was at the Montmartre, the then well-known jazz club in Lorne Street. I think this photo was from the wedding function.

The sitar belonged to Raman Bhai, he gave it to me to play – as long as I wanted to. He taught me some basic raagas of Indian classical music. He was a Fijian Hindu, and he had a fruit and vege shop on Ponsonby Road. I used to visit him there every Tuesday evening. He never charged me.

These were unforgettable times, my first taste of the discipline. He told me to rise early, take nothing but a little hot water, and then practice the sitar. I followed that quite faithfully. One morning, I was suddenly shocked to hear the beauty of what flowed from my fingers; I realised it was something latent, yet it felt that I was hearing it for the very first time… and once heard, it’s never forgotten. At that time, it felt very difficult to put the instrument down, I felt as though I could play it forever.

On the occasion of this photograph, my ability in Indian music was extremely basic – in fact, it still is. Yet, although my ‘performance’ was virtually something like the music of a child practising, the audience was welcoming and encouraging. It was a significant moment, as all such humbling moments are.

What else were you doing at that period? What was your background?

I had somewhat ‘grown up’ on Western music. In Dargaville I had an excellent jazz guitarist, Marsh Calkin, as my first teacher. I was utterly enchanted, associating with a real musician for the first time in my life. He forbade me to play the local dances for one year while I studied with him, telling me it would spoil me. In many ways I saw his wisdom to be sound. I am ever grateful to Marsh for that wisdom.

Moving to Auckland, I went directly into playing music full-time. I was so fortunate due my intimate friendship with Mike Perjanik – we were schoolmates. Mike had already entered the professional music field, and he didnt rest until he pulled me in with him.

There, in the group The Embers, we played as resident band at The Shiralee, later called The Galaxy. We also toured with Howard Morrison, Dinah Lee, Peter Posa, Bill and Boyd, The Chicks, John Hore, Lyn and Christine Barnett. Also Sandy Shaw and The Pretty Things and many others, as well as recorded extensively. Later I joined the Keil Isles who were resident group at the Oriental Ballroom, and played alongside Jimmy Sloggett – Jimmy and I had become close friends. After that I worked with vocalist Tommy Adderley as his guitarist, and also wrote his charts and toured with him extensively.

That was about the time I fell in with Bob Gillett, alto and tenor saxophonist, and we founded The Brew. Tommy Ferguson was our singer par excellence, while our drummers and bass players changed like a game of tag.

Bob was always inclined to higher thought and spirituality, as well as – as my intuition always told me – a true conception of musical excellence. It was by his influence that I ventured to approach the sitar.

What took you overseas and how did the Jesse Harper persona come about?

Reaching the age of 25 or 26, I felt a powerful pull to leave NZ and see the rest of the world, perhaps even go to India. Somehow I had an innate attraction for India, and how much of that was based on the charm of the classical music of India – or the many searching discussions I had had with Bob Gillett – is not perfectly clear. Probably a combination of all the above.

When I played sitar at the Gandhi Hall with Raman Chhibba, as I had mentioned my desire to him, he told the people there that I was going to India. They immediately passed a hat around, and my whole fare for a flight to India was suddenly thrown into my lap! But I used the money to go to UK.

Although my conviction to get to India was not forgotten, going to UK was something of a digression; and where would the money now come from, now that I’d spent it on getting to the UK? This posed something of a dilemma in my heart, causing me to wonder whether I was at all sincere regarding getting to India – my mind suddenly seemed lamentably flickering and weak…

Nonetheless, here I was in UK, so had better make the best of it. So I recorded the ‘Jesse Harper’ album during this period. The World Band was founded spontaneously and we moved to Holland. Shortly after that the money for the journey to India materialised with virtually no effort on my part.

Evidently, you chose to travel to India rather than ride things out in the UK. Did it bring the fulfillment expected?

Fairly often these days folks ask me about my making a decision to follow a spiritual path by going to India. I don’t see it this way at all. Perhaps I did to some degree at that time – but it was more a natural progression, a flow, rather than any such calculated decision. Otherwise how could it be anything spiritual? Again, ‘spiritual’ is a word that is shrouded with confusion and mystery… and ‘a spiritual path’ implies that there are hundreds and thousands of paths, another confusion and dilemma in the human society and worldview. Perhaps ‘being’ is an easier word in English, when attempting to describe a thing that is as natural and simple for the people of India as the act of drinking water.

So I arrived in India on 1st January, 1973. I breathed deeply with every aspect of my being. I can call it ‘existential relaxation’. Music was, and is always meant for self-realisation and the realisation of inner and outer peace, love and happiness.

You remained in India for many years. Why did you return to NZ when you did and how difficult was it for you to reconnect?

By 1981 I had met a most venerable teacher, with whom I discussed the importance of seeing my mother. He was very gracious and advised me to make a visit – I hadn’t seen my mother for 15 years. Hence I made my first return visit back to NZ, perhaps around 1982. I was stunned, seeing the beauty of NZ with new eyes, and felt my deep roots. It remains a most joyful experience.