Tutors’ Tutorial: Introduction To Microphone Technique

Tutors’ Tutorial: Introduction To Microphone Technique

This article on microphone technique briefly outlines how common microphones ‘hear’ and how to avoid some typical pitfalls when using them. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll be focusing specifically on the cardioid directional microphones such as the Shure SM58.

Cardioid microphones are a type of pressure gradient transducer, which is to say that they respond to sound pressure differently from different directions. This is very important to consider, whether using a microphone on stage, or positioning a microphone in a studio.

Polarity

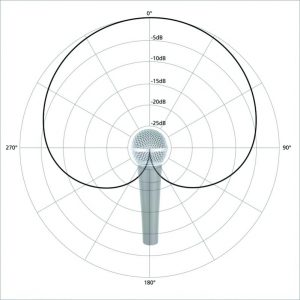

The term cardioid references the way in which these microphones pick up sound – reminiscent of a heart shape – and can be seen in a microphone’s polar pattern chart which is usually supplied by the manufacturer. The chart defines the front of the microphone as 0° and the back as 180° while everything else is more or less in the sides. The heart-shaped line tells us that if a sound is being produced anywhere other than 0° on-axis with the microphone it will be quieter, even if it remains at the same distance.

This is no accident. It’s the result of phase interference purposely created by ports built into the microphone’s design that essentially collapse sound in on itself proportionately to how off-axis the sound source is. The closer the sound source gets to 180°, the more it gets rejected and the less we hear in the resulting signal. Simply put, this means we can position a cardioid mic to maximise its sensitivity to a desired signal and minimise unwanted ‘noise’.

Position

If you are holding a microphone on stage for instance, it’s important that you avoid carrying it in front of the front-of-house speaker system as this may put those speakers on-axis with the microphone that is feeding them. This creates a positive feedback loop which in turn has a pretty negative effect on a performance!

Likewise, the back-rejection offered by a cardioid microphone is avoiding the same problem as long as it’s pointed away from your fold-back speaker. Be careful not to point it down towards this monitor.

The phasing ports are towards the back of the microphone capsule and can be disrupted themselves if they are covered. This tends to happen when people get too hands-on with a microphone and ‘cup’ its capsule. This actually makes the microphone omni-directional, meaning it can pick up sound equally in all directions, potentially causing a feedback loop with a speaker it had previously been rejecting.

The happy heart-shaped pattern we associate with a cardioid microphone actually skews above or below the frequency it references and can change dramatically at more extreme frequencies. This means we can position a cardioid microphone off-axis to a sound source and it can be quite a powerful way of colouring a sound. Try experimenting with this when you get a chance.

Having a sibilance problem? Sibilance is a surplus of high frequency energy often encountered when someone says something with the letter ‘s’. Try pointing your microphone somewhat off-axis with the person’s mouth by pivoting the capsule. This can significantly diminish the problem.

Proximity

The phasing ports also react differently at different distances. For instance, if you get very close to a cardioid microphone it begins to struggle with higher frequencies as they are increasingly rejected. This is called the ‘proximity effect’. It may sound like an improved bass response but in reality it is just a diminished fidelity which is difficult to fix, so try to avoid ‘eating’ a microphone – you really don’t know where it’s been anyway.

The other thing to be mindful of with regards to proximity is your volume. The microphone is feeding into an amplifier in the mixing console which your soundie has set carefully. Singers may change their volume throughout a performance for the sake of expression and that’s great, but one needs to be mindful of how this is being reproduced. The best thing to do is get closer to a microphone when singing/performing quietly, and pull away when getting loud to avoid distortion and a grumpy technician.

There are varieties of cardioid such as super-cardioid and hyper-cardioid which offer alternative polar patterns you might want to consider – not to mention non-cardioid patterns – but hopefully this has a been a useful introduction to microphone technique.

Marcel Bellvé is a Course Co-ordinator at Auckland’s SAE Institute. You can e-mail him at m.bellve@sae.edu