Moments Like These: John Dix

Moments Like These: John Dix

When were these photos taken and what were you all doing?

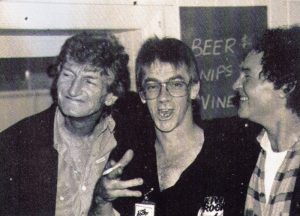

The colour photo is with Johnny Cooper, the Maori Cowboy, whom I’d known for many years, long before Stranded. The lovely young lady is Melissa Balducci, my PA. The other pic is of the Tommys, Adderley and Ferguson. Despite my seemingly high spirits, it wasn’t a good time and I was up early the next day, cancelling flights and advising musos. I caught Kevin Borich heading out the door in Sydney and I managed to contact Dave Russell at Melbourne Airport! It was one of the worst days of my life. A lot of bands had reformed and rehearsed so Hugh and I weren’t too popular for a while. Still, something was salvaged – Max & the Meteors played the Gluepot, their first NZ performance in 24 years. Ray Columbus & the Invaders did a couple of gigs, Bruno hosted a Blerta reunion at Waimarama and the Flying Nun concert went ahead at the Powerstation. As Hugh says, “We were before our time.”

Despite my seemingly high spirits, it wasn’t a good time and I was up early the next day, cancelling flights and advising musos. I caught Kevin Borich heading out the door in Sydney and I managed to contact Dave Russell at Melbourne Airport! It was one of the worst days of my life. A lot of bands had reformed and rehearsed so Hugh and I weren’t too popular for a while. Still, something was salvaged – Max & the Meteors played the Gluepot, their first NZ performance in 24 years. Ray Columbus & the Invaders did a couple of gigs, Bruno hosted a Blerta reunion at Waimarama and the Flying Nun concert went ahead at the Powerstation. As Hugh says, “We were before our time.”

What was your earliest awareness of music, and what got you started in writing about it?

I organised regular bus trips to Cardiff to see the Stones (twice), the Beach Boys, Hendrix, and the big one for me – the Stax Volt Revue with Otis Redding, Sam & Dave and co., probably my most memorable concert. I was a hopeless student, too easily distracted, but I had a talent for writing, the only thing I excelled at, and I was contributing to the local rag when I was 14.The family emigrated to Adelaide in 1967 and I wrote for the Daily News and Go-Set magazine while working for a booking agency, organising weekend dances. I was young and it was fun; it was only later that I realised I should have been getting paid a lot more. The better Adelaide bands gravitated to Melbourne or Sydney, and my preferences ran to black American music and I was a total fucking snob.

After all, Id seen the Stax Volt Revue! So I had that supercilious attitude of …they’re pretty good for an Aussie-band. That is until I saw Max Merritt & The Meteors in 1968. Max became my teenage hero, the coolest white man on the planet.

What was the catalyst for writing Stranded in Paradise? How you were able to consider such a huge endeavour?

Two friends, Diane Kearns and Max Rees, assembled a team to put the book together. Diane managed proceedings, Max was in charge of design. It was early days of desktop publishing and we were all amateurs – we had an Apple Mac and a computer whiz plus a typographer, a design team, a runner for typesetting and bromides, and a whole swag of mates as proof readers, including Bruno and Bill Direen. Fane Flaws dropped in one day to add his touch (the Swinging Sixties chapter, all Pop Art, is Fane’s contribution). I presented David Ortega, a Polytech student, with a selection of Rick Bryant pix and he did the cover.The second edition was published by Penguin. In between signing the contract and the book’s release, I became caregiver to my mate Bill Payne, writer and poet, who required a liver transplant. I thought it would be a piece of piss but, unfortunately, Bill’s body wasn’t up to it and at a time when my focus should have been on the book I was wondering if my mate was going to last the month. A lame excuse maybe but the book no longer seemed important.

Finlay MacDonald at Penguin was very supportive and he did much to ensure that the book came out. I signed off the galleys at Auckland Hospital, where Bill was having his 10th or 11th life-saving operation, and later discovered the mistakes, obvious ones which I should have picked up, but I guess I was too distracted. Bill died six weeks before the Penguin edition was released.

Where did you find the line ‘stranded in paradise’?

Stranded in Paradise could be considered to mirror a similar destiny that surrounds a plethora of NZ slow selling LPs and singles. Did the effort and expectations impact on your career?

Did it change me? I guess so. The reviews were positively glowing, that took me by surprise. I figured the music media would like it but not the mainstream book reviewers. Out of 50-odd reviews there was only one negative – David Cohen in the Evening Post. He called me a sycophant and said it was badly written and poorly researched. My publishing partners were outraged but I thought it was a hoot. We had great reviews in every major NZ publication plus the Melbourne Age, Sydney Morning Herald, several overseas fanzines and even Greil Marcus in the Village Voice.I have always stressed that Stranded was an attempt to paint the big picture. It’s amazing the number of musos who hit me up, complaining that they didn’t feature – I still get it today. But these people only read the index, they certainly didn’t read the introduction.

I mentioned, and this is a no-brainer, that there were a dozen books or more about various aspects, eras or genres of NZ music. The first one came out within months – Roger Watkins’ When Rock Got Rolling, covering the Wellington ’60s scene – and now, of course, there are heaps out there, although few if any the equal to Chris Bourke’s Blue Smoke.

Is that Stranded’s legacy? It would have happened anyway and, besides, Stranded was not, strictly speaking, the first such book. In 1964 or ’65 John Berry wrote Seeing Stars, a collection of profiles on NZ and visiting performers, from Sir Howie to Satchmo. But, yes, I’m aware that Stranded is the benchmark by which other NZ music books are judged.

There must have been times when you thought, ‘What am I doing this for?’

You’ve remained prolific and industrious, what are some of the other writing and music projects you’ve been involved with?

Okay, since Stranded in 1988: I was employed by The Gluepot. I worked on all five Mountain Rock Festivals, founder-editor of Real Groove magazine (they, Real Groovy Records, wanted to call it Maverick. Maverick?). Had my own Queenstown music venue. Established a South Island tour circuit and spent five years at Parihaka Pa as an administrator of the Parihaka International Peace Festival, the best gig I have ever worked on. Few have anything in common, and the difference between Mountain Rock and Parihaka is budget – difficult to get a sponsor if you’re not selling alcohol.I have never considered myself a fulltime writer and I have always pursued other employment. Promoting and tour managing has featured prominently, and I worked in radio for five years, believing that I could actually affect change in that industry. Some hope – it gets worse by the year.

In my younger years I worked in shearing sheds, a railway gang, a biscuit factory. Last year I helped a mate on a project in Te Awamutu, time trialling a new device, filming milkers twice a day, up at 4am every morning, seven days a week for three months. In Te Awamutu! I can understand why the Finns rarely return.

What’s the best book on music you have read?

Mystery Train by Greil Marcus. My original concept for a history book was largely based on Mystery Train. Such an approach would have spared me the task of writing up artists whose success I don’t endorse. Marcus chose 20-odd acts and told their story, from the obvious to the obscure; each was self-contained but, as a whole, the book covers the whole of rocknroll. I still think it’s the best book written on rock music, although I have to mention Stanley Booths, The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, an intriguing if tragic subjective account of his experiences. Spend 12 months with the Stones and become a junky!

What’s your take on the changes and challenges in publishing today?

I’m still coming to grips with new publishing technology. I’ve had several approaches re an e-book edition of Stranded and I am considering one right now but with a big difference – not one volume but six, each covering a specific era, starting with the years 1955–1962. This would allow me to go past the big picture and really explore and celebrate the music-makers of each era. Early days yet and I’ve yet to make a decision. I’ll keep you posted.

Your favourite NZ song?

One song? Poi E, probably, all things considered, and maybe Heavenly Pop Hit runner-up.

What’s the most meaningful thing that you’ve experienced so far writing about Kiwi music?

It’s only rock’n’roll…

The best advice you ever got was?

Close the door.