X-Factory: Mel Parsons – Sabotage

X-Factory: Mel Parsons – Sabotage

Award-winning singer/songwriter Mel Parsons has developed a loyal fan base since releasing her debut album ‘Over My Shoulder’ in 2009. Her unique vocal tone, delicate guitar playing, and introspective songwriting have won her fans in Aotearoa and abroad while also clocking up a number of NZ Music Awards, including Best Folk Artist (2020) and Best Country Music Song in 2016. Her sixth studio album ‘Sabotage’ continues in a similar tradition, featuring a collection of songs that feel raw, honest, and often confessional. A finalist for the 2025 Taite Music Prize, the album was also a finalist nominee for the AMA Folk Artist and Album of the Year awards.

The title track Sabotage is hauntingly beautiful, featuring Parsons’ trademark rich and sonorous voice overtop of gentle acoustic guitar, gorgeous backing vocals, and stripped-down production. It’s also a great example of musical prosody, which essentially refers to the ways in which the nature of the music enhances the meaning or theme of the lyrics.

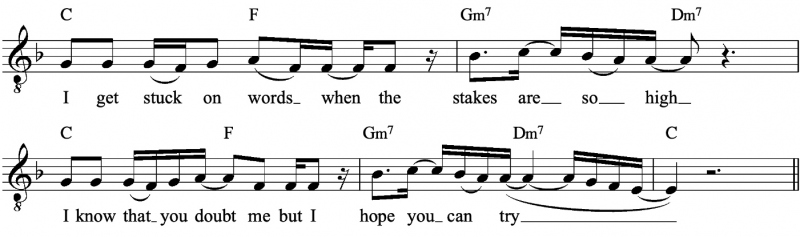

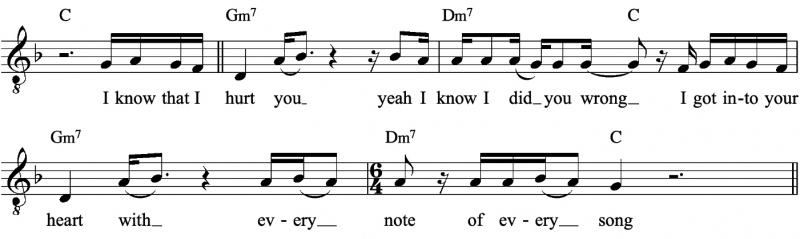

As a concept, ‘sabotage’ is inherently unstable, a volatile act of destruction that can be directed at others but also at oneself. Sabotage is not a concept that one would likely associate with feelings of security, predictability, or harmoniousness. Building on this, consider the opening lyrics; ‘I get stuck on words when the stakes are so high. I know that you doubt me but I hope you can try. I know that I hurt you, yeah I know I did you wrong. I got into your heart with every note of every song.’

These are not stable concepts such as those found in songs about love, joy or triumph. Instead, they speak to things like regret, isolation and self-doubt, like a lost wanderer looking for salvation, or at least some kind of resolution. So given an unstable title and unstable lyrical themes, let’s look to see how this instability is further enhanced by the music.

Fragile Tonic

The thing that first caught my attention is the lack of a stable tonic. Sure, it uses notes and chords from F major but it doesn’t really feel like it’s in the key of F major, or any of its related keys such as D minor or G Dorian. The reason for this is that, although the F chord makes several appearances, it never lands where one would expect a tonic chord to land. Beginning a chord progression on the tonic chord sounds grounded, assured, like we’re starting from home. Ending a progression on the tonic chord feels complete, resolute, like we have concluded our journey and are back at our resting place. Sabotage does neither of these.

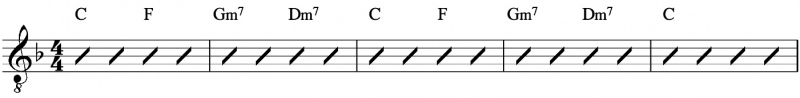

The intro/verse progression begins on the dominant chord before resolving to the tonic at a metrically weak point before quickly moving away, creating a feeling of brushing up against the tonic rather than landing on it. The harmonic loop concludes with a Gm followed by Dm but again, neither of these chords are given strong metrical placement that might suggest a tonic chord. The progression then repeats starting back on the dominant chord, however this time it also concludes on the dominant chord; instability moving towards more instability.

Fig. 1. Intro/verse chord progression

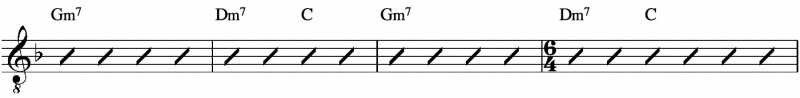

One might expect the dominant chord positioned here to act as a cadence into an F major or D minor chord at the start of the next section but no, the pre-chorus progression doesn’t include an F chord at all and the relative minor Dm, while present, is similarly buried in the middle of the progression.

Fig. 2. Pre-chorus chord progression

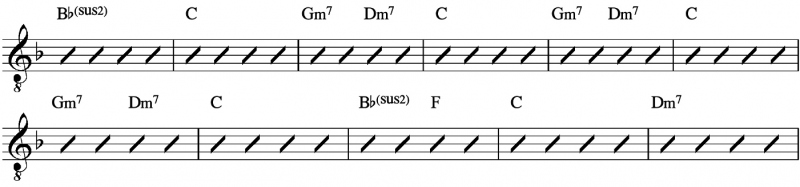

Like the verse, the pre-chorus ends on the dominant chord, setting up the expectation of a cadence to the tonic chord at the top of the chorus, but again this expectation is subverted. The chorus progression begins on the IV chord before moving to the V, suggesting a IV – V – I cadence but instead sets up a repeating ii – vi – V loop that never seems to land anywhere. The end of the chorus is perhaps the briefest moment of tonicization that Sabotage affords, setting up a IV – I – V cadence that resolves to the vi with a brief suggestion that we were in D minor all along, however the song quickly breaks away to the second verse to repeat the harmonic progression from earlier.

Fig. 3. Chorus chord progression

So, although the song exclusively uses notes and chords from the key of F major, the F chord itself is never given a priority position within the harmonic progression, rather it is obfuscated in the middle of the phrase. Drawing from the same pool of notes could also give a key of D minor or G Dorian, but neither the Dm or the Gm chord feel like the tonic for the same reason; when they occur they are almost always hidden in the middle of a harmonic phrase.

This technique, where the tonic chord is present but placed in weak positions of the progression, creates what is known as a ‘fragile tonic’; there is some sense of home but it is fleeting and unstable, and in Sabotage this instability perfectly enhances the unstable lyrical themes. On a side note, ‘absent tonics’ are also possible, where the tonic chord is never played, as are ‘emerging tonics’ where the tonic chord is delayed until later in the song and only then suggests a home key.

Asymmetrical Phrasing

Another thing that further contributes to the feeling of instability is the harmonic phrasing of each section. Notice how they’re all asymmetrical? Parsons has done away with a typical 4 (or 8 or 12 or 16) bar structure and used phrases with an odd number of bars that highlights the instability and unpredictability of the chords. The intro/verse progression (fig. 4) is five bars long and the vocal melody initially creates two two-bar phrases but then expertly threads the fifth bar onto the end.

Fig. 4. Verse vocal melody

The pre-chorus (Fig. 5) is four bars long but the final bar has a 6/4 time signature, creating an impression of an extra couple of ‘floater’ beats attached to the end of the final bar.

Fig. 5. Pre-chorus vocal melody

The chorus (Fig. 6) also forgoes a typical symmetrical structure, instead using an 11-bar chord progression that feels like it’s standing on shifting sands. Also note the final C chord of the chorus and how it’s almost begging for a final iteration of the title, only to be left hanging, like an act of sabotage itself.

Fig. 6. Chorus vocal melody

Stable/Unstable

Stable/Unstable

So, with all this instability going on to reinforce the unstable lyrical themes, you may wonder if there’s anything inherently stable about the song. Instability is a powerful compositional tool but like all tools it can be overdone. Mel Parsons balances this perfectly with the highly stable vocal melody.

Note how balanced the melodic phrases are and how they are closely connected to the underlying chord tones (Figs. 4-6). All of the metrically strong notes in the melody are chord tones and the non-chord tones always resolve by step to chord tones. This has the effect of creating a strong connective tissue between the melody and harmony, and balances out the instability found in other areas. Likewise, the relatively flat texture and steady drum groove, devoid of even a single fill, help give the song a sense of stability to balance out the shifting harmony.

Sabotage is a beautiful song, captured with a beautiful performance, that elegantly uses instability in the musical patterns to enhance the unstable lyrical themes while providing just enough stability for balance. This is a great demonstration of prosody in action.

Jeff Wragg composes popular and classical music, and also composes for film, television and theatre. He is also an educator and has held teaching positions at MAINZ, SIT and Victoria University. He can be contacted at www.jeffwragg.com