Deep Thinking: Using The Pentatonic Scales

Deep Thinking: Using The Pentatonic Scales

The last couple of Deep Thinking columns that featured one of Jaco Pastorius’ best pieces (IMHO) have maybe made the learning too difficult for bassists, so in this column, I am going right back to some simple stuff that’s still in use in all avenues of popular music, and used by beginners as well as some of the best players around – the pentatonic scales.

Coming from the Greek for ‘five’, the pentatonic scale comes in minor and major progressions of five notes. (We will look at the major one in the next column.) The minor pentatonic scale can be bluesy, jazzy, rocky and just about anything else depending on how it is used. And, before anyone gets critical of its simplicity, check out some of the finest ‘classical’ (I hate that bland word) composers and listen to how they have used pentatonicism, including one of my favourite composers, Claude Debussy. What I mean is that not everything has to be chromatic to sound good!

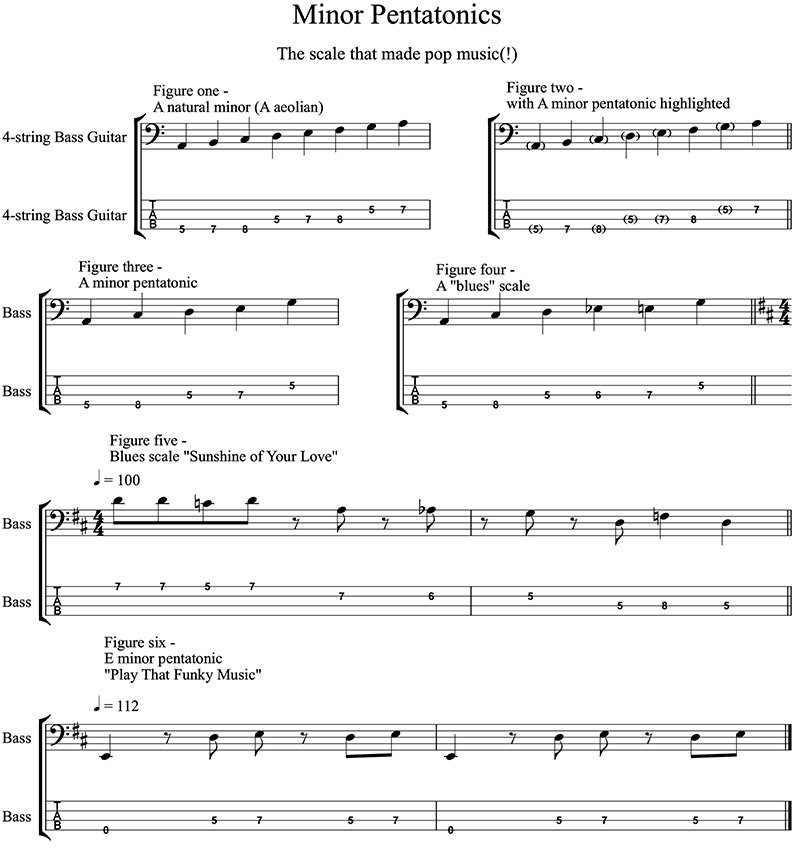

Figure 1 is an A natural minor scale. It comes from the sixth step of the C major scale and is also known as the Aeolian mode. I will be looking at modality in a later issue but the C major scale is also known as C Ionian and modes can be built on each of its steps.

This modal system can be applied to all 12 keys in standard Western harmony, I’m just using C major because there are no sharps and flats (known as ‘accidentals’) to get in the way! If we take A, C, D, E, and G (bracketed in Figure 2), these are the minor pentatonic notes.

In figure 3, we start on A at fret 5, string 4, moving up to fret 8 for the C, changing string to string 3 and playing D at fret 5 and then E at fret 7. Finally, we play a G at fret 5 on string 2 and there you have it, an A minor pentatonic scale.

I used to be a bit snobby about this scale years ago, saying that Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler would be as poor as church mice if not for this scale, but there are millions of musicians and music fans out there that proved me wrong! To make the scale more bluesy, play a passing note, a flat five (Eb) between the D and the E.

This is often known as the blues scale. When soloing you can start anywhere in the scale but if you are holding the band’s groove together, stick around the A (if the band are using A major or A minor chords because it works for both) and use the other notes to build a line or a riff.

In Figure 4, I have included Jack Bruce’s classic bass line from Sunshine of Your Love from ‘Disraeli Gears’ (1967) to demonstrate the blues scale. The song is in D but the riff moves through the song almost as a 12-bar blues.

Lastly, Figure 6 has the bass line to Play That Funky Music by Wild Cherry. It is very simple but, as the old saying goes, ‘…it’s what you leave out that matters’. Both of these tracks are on YouTube. Have fun and see how many of your favourite rock, funk and blues tunes use this scale. Until next time!

Dr. Rob Burns is an Honorary Associate Professor in Music at the University of Otago in Dunedin. As a former professional studio bassist in the UK, he performed and recorded with David Gilmour, Pete Townsend, Jon Lord, Eric Burdon and members of Abba. He played on the soundtracks on many UK television shows and is currently a member of Dunedin band, The Verlaines (new album, ‘Dunedin Spleen’), and features on three new Seelie Court Records (UK) progressive rock albums released in the UK since 2020.