Ex-pat Files: Bruce Aitken

Ex-pat Files: Bruce Aitken

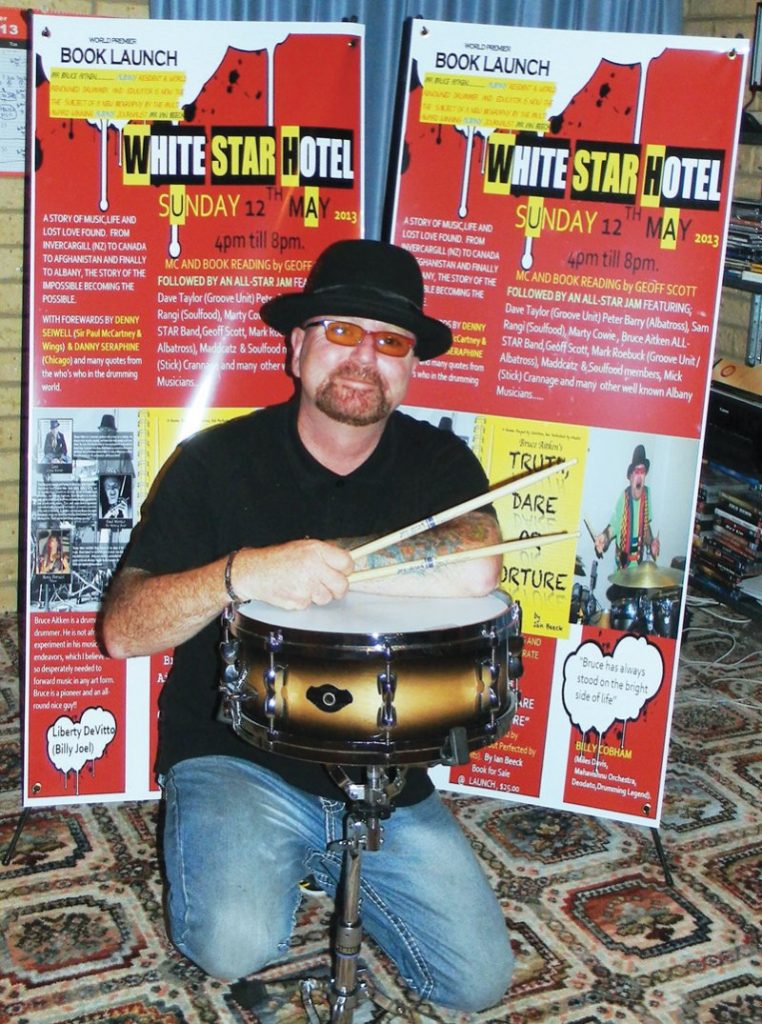

Certainly he’s not beyond self-promotion, but it’s likely that Bruce Aitken wouldn’t rate himself as one of this country’s better, or even better known drummers. Yet this self-described “pint-sized bespectacled lad from Invercargill” has seemingly befriended and played alongside more of the world’s finest beat keepers than our most famous drummers – of any era/genre – have. His trick was to create his own annual drum festival. And what a good trick it proved, with the Cape Breton International Drum Festival having a proud run of a full decade, culminating in 2010. (That’s him, far right in the photo above.) These days Aitken lives in Western Australia, from where a tell (nearly)-all book entitled Bruce Aitken’s Truth, Dare or Torture was recently published.

Born and raised in Invercargill, Bruce Aitken was an early adopter of the drums, taking to the stage with his first band, Rogers Dodgers, at primary school. In the very autobiographical book of his life, Bruce Aitken’s Truth, Dare Or Torture, he labels it the country’s youngest beat group.

Shifting to Wellington with his family in late 1969, he recalls the music scene there as being “just incredible”. Among the Kiwi rock-era bands most important to his own career development Aitken lists the Underdogs, Dizzy Limits, Quincy Conserve, Split Enz, Dr Tree, Space Case, The Crocodiles, Sons and Lovers, Toy Love, Red Eye and Blerta.

“Although I have never seen Split Enz nor Dr Tree live, the music, especially that of Frank Gibson Jr, made me really take stock of what I was all about. I remember seeing Dizzy Limits with Steve McDonald on drums and vocals at a surf club in Paekakariki and was just blown away with his playing and showmanship, it just made me want to learn more. Anything the late Mal Hayman (Quincy Conserve) did was world class. We were great mates, didn’t have to look much further to learn there. I guess they were all larger than life.”

Bruce Aitken was to spend the next two decades playing mostly around the greater Wellington region with all manner of bands and acts, though never quite making the A-league. He props plenty of other fellow musicians from those days.

“Richard Waitai, Kemp Titirangi, Hari Kamaru, Wayne (Hair) Tairoa, Paul Waitai, Evan MacGregor, Tommy Swainson, Murray and Fred Loveridge, Ray Columbus, Billy T, Glenn Pigg, Tom Perry, Billy Brown, Danny Shaw, Bruno Lawrence, Fane Flaws, Tony Backhouse. The list is endless, but the most exciting guy I saw back in the day was Darren Watson, his band Smokeshop just blew me away.”

Aitken started teaching drums in the early ’80s, in response to fellow musicians asking him to show their kids how to play.

“I was more than happy to share and encourage them to be themselves. Mind you I did also share lots with other kids when I was growing up in Invercargill. I just love teaching, its a passion and one Ill never tire of.”

It was that kind of passion that led to his life-defining role as the founder / organiser of the Cape Breton International Drum Festival, from 2001 – 2010.

Cape Breton is an island off the east coast of Canada, not a long flight from New York, but literally miles from nowhere. Aitken won’t be drawn on what took him there, but once ensconced in the small and evidently parochial community he was soon teaching drums. The island didn’t have a local music festival, let alone an international one, but once he’d hit on the idea as a profile raising exercise found the small population and remoteness a selling point.

“Strangely enough that’s one of the reasons it did work, its location. Big cities generally have many things to see and do. In smaller locations a whole community can become involved, and the opportunity I afforded them with the calibre of talent I bought to the island worked wonders, not just for the music community, but also for the region financially.”

There were major drum festivals already well-established, nearish-by Montreal and New York among others, but Aitken brought a personal touch and Kiwi #8 wire-magic to his that set his apart from others. The edge-of-the-world location was one drawcard, but what else made it special for so many pro drummers?

“The way I treated all as equals. The production. Knowing the drummers’ history – I never read off notes ever when introducing artists. Honesty, and my passion for drums and education. And of course, the hang. Lets’ face it, where are you going to see so many of the world’s most iconic drummers in one place at one time for a whole three days? You have to realise that many of these truly incredible and influential drummers don’t always know each other personally, so it was a win-win situation for everyone.”

Aitken also took advantage of emerging technology to make his festivals a more user friendly experience. Soundchecks were all done ahead of playing times, with computerised desks used so the drummers could sound check in any order. Big screens, power point presentations and so on.

“There were many things. I was full of ideas to make each festival different each year and special for each of the performers. Never the same formula any year, always a different theme, I always had them guessing and they loved it. Even little things – like different badges for the drummers each year – personalised stuff. I looked after all the little things, the important things. I cared that each drummer was treated with the respect they deserved, and some.”

As well as hosting, and sometimes playing with a long list of drumming luminaries, Aitken says that he learnt from each drummer, each festival appearance.

“There was never one performance in the whole 10 years where I didnt learn something. Quite frankly you can never stop learning, it’s never too early and its certainly never too late.”

It reinforces his own enthusiasm for teaching, and indeed many local drum students also got the chance to perform at the Cape Breton festivals, the consistent theme being education through performance.

“There is something to be learnt from everyone, be it a world-renowned drummer or be it a student. The drums are so personal, everyone has their own sound – everyone brings something new to the table, that’s why drummers are such a very special group of people.”

International festivals are costly things to run, not just financially, but emotionally and physically as much. It’s little surprise that although only in his 50s, Aitken has suffered two major heart attacks, had open-heart surgery and endured some even heavier personal costs.

International festivals are costly things to run, not just financially, but emotionally and physically as much. It’s little surprise that although only in his 50s, Aitken has suffered two major heart attacks, had open-heart surgery and endured some even heavier personal costs.

“It was never about money, it was a non-profit thing. Top priority for me was [that] you must share what you know so that others can pass it on. All my mates, who play in the many of the biggest bands or acts in the world, teach when not on the road. We love our chosen instrument and want to keep it going, inspire and mentor up and coming musicians. It’s an amazing feeling to see former students doing well, and just as amazing to see any student develop in their own space, both are equally as important.”

The comments and credits proudly included in his book from a variety of participating drummers (Zoro, Paul Wertico and Roxy Petrucci on the back cover alone) reveal the real pleasure even established stars found in Cape Breton. Aitken made sure that he got to play alongside as many of them as possible, giving himself some priceless memories. He’s typically generous in his praise and rates many drummers highly, so when asked who was the most effortlessly talented drummer he came across, the list again isn’t brief.

“Denny Seiwell, Bill Bruford, Bill Cobham, Zoro, Paul Wertico – they would all fit that category. Others would be Jim Keltner, Hal Blaine, Bobby Graham, Bernard Purdie, Jim Gordon, Steve Gadd… And without a doubt one of my greatest ever mates, the late Uriel Jones from The Funk Brothers. Sometimes he played nothing, but he played nothing so darn well and effortlessly.”

Aitken is very proud at having been inducted into the Southland Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2008 and of his appearance on the cover of short-lived Kiwi drum magazine, Connexions. At that time he did a series of drum clinics here and reckons that any budding musicians who miss such free learning opportunities is crazy.

“No one musician/person knows everything, so grab what you can from everyone. So it should be at the top of the list in my humble opinion. Then start using your imagination. I have been very fortunate to have done a clinic tour of NZ in 2006, and have to admit my clinics were very well attended, but I do know that’s not always the case. (One time recently Steve Gadd played to just 10 people in New York).

“When an opportunity arises to see and listen to any clinician regardless of what they play or who they play for, you really must take that opportunity. You can never stop learning, or get inspired to do what you do to the best of your ability. There is no such thing as the best, just the best you can be.”

He well remembers the very first drum clinic he attended, in the old musicians club in Wellington.

“The legendary Roy Burns was the clinician. There must have been two people tops, or was it three – Roy played like he was in front of a million. I remember thinking after he did two completely different solos, how could one person have so many ideas? It was a wake up call. I emailed Roy when I was in Canada, telling him I’d seen him in Wellington all those years ago and what a huge impact it had on my thought process.

“Then about 10 minutes later the phone went, and it was Roy. We talked for ages. Who would have thought huh?”

These days living in Albany, Western Australia, Bruce Aitken remains active as a player, and more importantly, a teacher. By now he has his basic messages down pat.

“Be a servant to the song, learn to read, listen (have big ears), and be humble, reliable and honest. Know the history, know your instrument, and be willing to get on with fellow musicians. This sometimes is more important than being a hot shot (which I’m not). Groove, groove, groove. It’s all about the pocket (feel).”